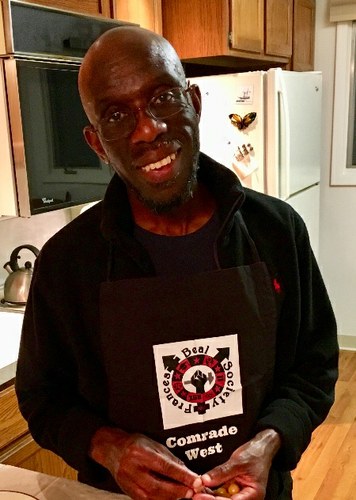

Professional Bio

I am currently working on a book on Kwame Nkrumah and the Global Black Power Movement of the Long 1960s

Research Interests

Black social movements and struggles in global persepctivesRelated Materials

Even as symbols of Africa permeate Western culture in the 1990s, centers for the academic study of Africa suffer from a steady erosion of institutional support and intellectual legitimacy. Out of One, Many Africas assesses the rising tide of discontent that has destabilized the conceptions, institutions, and communities dedicated to African studies. In vibrant detail, contributors from Africa, Europe, and North America lay out the multiple, contending histories and perspectives that inform African studies. They assess the reaction against the white-dominated consensus that has marked African studies since its inception in the 1950s and note the emergence of alternative approaches, energized in part by feminist and cultural studies. They examine African scholars' struggle against paradigms that have justified and covered up colonialism, militarism, and underdevelopment. They also consider such issues as how to bring black scholars on the continent and in the diaspora closer together on questions of intellectual freedom, accountability, and the democratization of information and knowledge production.

By surveying the present predicament and the current grassroots impulse toward reconsidering the meaning of the continent, Out of One, Many Africas gives shape and momentum to a crucial dialogue aimed at transforming the study of Africa.

Tracing their quest for social recognition from the time of Cecil Rhodes to Rhodesia's unilateral declaration of independence, Michael O. West shows how some Africans were able to avail themselves of scarce educational and social opportunities in order to achieve some degree of upward mobility in a society that was hostile to their ambitions. Though relatively few in number and not rich by colonial standards, this comparatively better class of Africans challenged individual and social barriers imposed by colonialism to become the locus of protest against European domination.

Transcending geographic and cultural lines, From Toussaint to Tupac is an ambitious collection of essays exploring black internationalism and its implications for a black consciousness. At its core, black internationalism is a struggle against oppression, whether manifested in slavery, colonialism, or racism. The ten essays in this volume offer a comprehensive overview of the global movements that define black internationalism, from its origins in the colonial period to the present.

From Toussaint to Tupac focuses on three moments in global black history: the American and Haitian revolutions, the Garvey movement and the Communist International following World War I, and the Black Power movement of the late twentieth century. Contributors demonstrate how black internationalism emerged and influenced events in particular localities, how participants in the various struggles communicated across natural and man-made boundaries, and how the black international aided resistance on the local level, creating a collective consciousness.

In sharp contrast to studies that confine Black Power to particular national locales, this volume demonstrates the global reach and resonance of the movement. The volume concludes with a discussion of hip hop, including its cultural and ideological antecedents in Black Power.

West, M. O. (2012). Little rock as America: Hoyt Fuller, Europe, and the little rock racial crisis of 1957. Journal of Southern History, 78(4), 913-942.

The struggle for Zimbabwe is coterminus with the commencement of the Southern Rhodesian colonial project, which was part of the larger European scramble for Africa in the late nineteenth century. Like everywhere else in Africa and beyond, colonialism in Southern Rhodesia centered on expropriation. That is, the expropriation of natural, mineral, and agricultural resources and the human labor that was needed to exploit those resources. This was not, of course, an enterprise that proceeded with the consent of the colonized. Colonialism—and the point bears emphasizing in the face of ongoing white-washing narratives to the contrary—was a violent process. Like African slavery in the Americas colonialism in Africa was imposed by violence and maintained by violence. The most potent symbol of European rule in Africa was not the vaunted schoolhouse of Christian missionaries, but the colonizer’s whip, that ubiquitous instrument that was everywhere deployed upon the colonized body—on the job, in the streets, in the prisons, even in the missionary schools and churches. This was indeed colonial slavery, as certain radicals took to calling it. The long-standing struggle for Zimbabwe, then, began as a struggle against terror, the systemic and systematic terror and violence of colonialism. This struggle was all the more vexed because Southern Rhodesia experienced colonialism of a special kind: settler colonialism.

The period between the two world wars was one of the most tumultuous in the twentieth-century history of Africa and communities of African descent in the North Atlantic world. The interwar years commenced with violence directed against black people worldwide, ranging from the suppression of strikes and other forms of popular discontent by colonial regimes in Africa to organized riots by white citizens in the United States and Europe. Egregious though these acts may have been, it was not the violation of black bodies, rights, and properties, whether by the state, "civil society," or the mob, that made the era exceptional. Violence against black people, however and in whatever name inflicted, had been a central feature of the Euro-African interaction since the advent of the Atlantic slave trade. What distin- guished the interwar period, rather, was a remarkable upsurge of political, social, and intellectual renaissance, both on the African continent and in the transatlantic dias- pora. Everywhere, local organizations found deeper and wider expressions, some- times giving rise to groupings that transcended colonial, national, and continental boundaries. Little wonder that the guardians of empire, territorial as well as racial, found themselves in a frenzy over the generalized "unrest among the Negroes," who were thought to be "seeing red."

This article examines the Million Man March in the wider context of black nationalism, a persistent, though inconsistent, factor in African American life, enjoying wider currency at some historical junctures than others. Those periods when black nationalism resonated strongly among African Americans are called black nationalist moments, four of which are identified here. The Million Man March, with its heavy inflection of patriarchy and black capitalism, is seen as the iconic event of the fourth moment. The subsequent Million Woman March is pivoted as a more radical and activist rejoinder to the Million Man March, a response continued by the even more recent Black Radical Congress.

West, M. O., Hill, L. W., & Rabig, J. (2012). Whose Black Power? The Business of Black Power and Black Power’s Business. The Business of Black Power: Community Development, Capitalism, and Corporate Responsibility in Postwar America, 274-303.

Direct and indirect links between the Indian subcontinent and Africa, particularly coastal East Africa, go back many centuries. Well before the era of European overseas expansion, the two regions were constituent parts of a kind of Indian Ocean political economy involving the transfer of goods, people, and various aspects of material and nonmaterial culture.∞However, this earlier commerce produced no recognizable Indian community on the African mainland.